Epidemiological Study of Gastrointestinal Conditions in St. Lawrence County Analysis 1: Examining Higher Severity Conditions

Epidemiological Study of Gastrointestinal Conditions in St. Lawrence County Analysis 1: Examining Higher Severity Conditions

Mark Bray & Shanna Bonnano

Abstract

Background

Abdominal complaints constitute approximately 7-10% of all Emergency Department (ED) visits in the United States.1 In St. Lawrence County, NY (SLC), abdominal complaints make up approximately 14% of 911 calls [2]. Yet, abdominal pain remains a vague and non-specific complaint, and to date, no study has examined the epidemiology of gastrointestinal diseases in SLC. We conducted a retrospective, descriptive, cohort study to examine and report anonymous, aggregated data summarizing inpatient discharges with a primary APR MDC Description “Diseases and Disorders of the Digestive System” in SLC hospitals from 2011-2017.

Methods

Data were obtained through the open-source hospital inpatient data (SPARCS de-identified) system on the New York Department of Health government website [3]. Case data included inpatient discharges of patients with an APR MDC coded as “Diseases and Disorders of the Digestive System.” Data were downloaded into Microsoft Excel sheets by year and aggregated by diagnosis for analysis.

Higher-severity diagnoses were determined by mortality rate and APR severity. These included “extreme,” “major,” and a selected group from the “moderate” rated APR level. For complete methods see Epidemiological Study of Gastrointestinal Conditions in St. Lawrence County: An Introduction” (specifically, Figure 1 in the report). The CCS diagnosis “abdominal pain” and “gastritis and duodenitis” were excluded from this analysis as these were considered symptoms rather than underlying diseases.

Results

Higher-severity cases constituted 44% (2657 admissions) of admissions to SLC Hospitals for GI conditions from 2011-2017. These diagnoses included: cancer of colon, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, intestinal obstruction, and intestinal infection. Hospital admission rates for these conditions were lower in SLC than nationally reported rates for colon cancer and GI hemorrhage but higher for intestinal obstruction and intestinal infection. The median length of stay for all 4 conditions was 3.75 days. The total cost for these 4 GI conditions was $23,721,085 or approximately $3,388,726 per year, which is 50.5% of the total cost for the 9 GI conditions we examined.

Conclusion

Among high-severity GI conditions in SLC, “intestinal infections” and “intestinal obstruction” had higher hospitalization rates than reported national rates. Both conditions were more prevalent among women in SLC. Intestinal infections had a mortality rate 6 times higher than national rates.

2.1 Results

2.1.1 Cancer of Colon

Patient Encounters of Cancer of Colon in SLC

There were 141 hospitalizations for colon cancer in SLC from 2011-2017. The incidence rate for hospitalization averaged across the 7 years in our study was 18 per 100,000 with the rate growing from 15 per 100,000 in 2015 to 26 per 100,000 in 2016 and 20 per 100,000 in 2017. Nationally, the incidence of colorectal cancer hospitalizations is 53.7 per 100,000 [24].

Patient hospitalizations by year are shown in Figure 2.1. Patient hospitalizations by year and gender are shown in Figure 2.2. Four percent (4.26%) of admissions resulted in a fatal disposition. The median length of stay was 6 days and the median cost of treatment was $14,031.

Median Age Range of Cancer of Colon in SLC

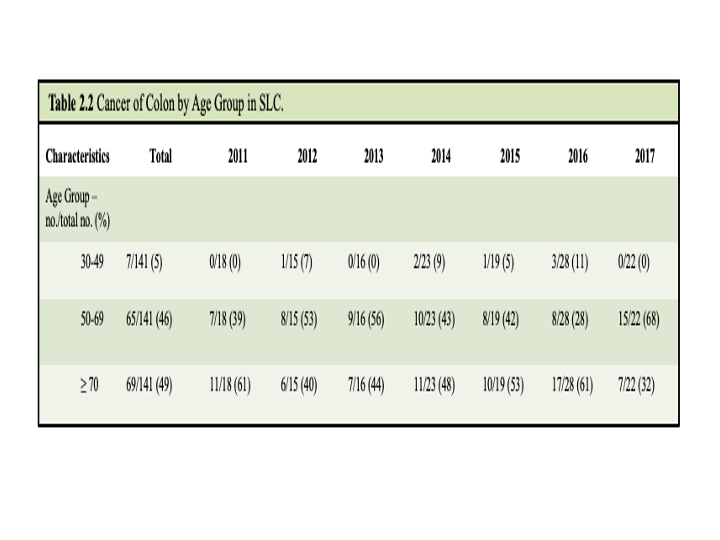

Colon cancer is associated with higher age, 49% of hospitalizations were with patients ≥ 70 years, 46% were with patients 50-69 years, and 5% were with patients aged 30-49 years. There were no hospitalizations recorded of colon cancer in patients less than 30 years.

The median age range of patients hospitalized with colon cancer in SLC across the dataset was 50-69 years; however, in years 2011, 2015, and 2016 median age was ≥ 70. The median age range in men was 50-69, whereas for women was ≥ 70. The data by gender are shown in Table 2.1 and by age in Table 2.2

1.1.2 Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage

Patient Encounters of Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage in SLC

There were 784 hospitalizations for gastrointestinal hemorrhage. The yearly incidence rate for hospitalizations averaged over the 7 years was 99 per 100,000. The national rate for hospital admissions is 161 per 100,000 [24].

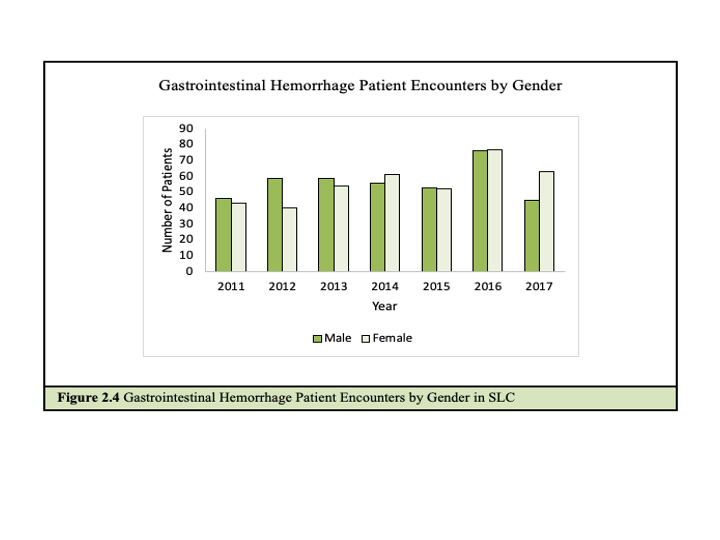

Patient admissions by year are shown in Figure 2.3. Patient admissions by year and gender are shown in Figure 2.4. The mortality rate of GI hemorrhage was 1.53%. The median length of stay was 3 days and the median cost of treatment was $6,744.

Median Age Range of Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage in SLC

Gastrointestinal hemorrhage was also associated with increased age. The median age range of patients admitted for GI Hemorrhage in SLC from 2011-2017 was ≥ 70 years. By gender, the median age range for men and women across the data set was ≥ 70 years with some variation in individual years. The data are shown in Table 2.3.

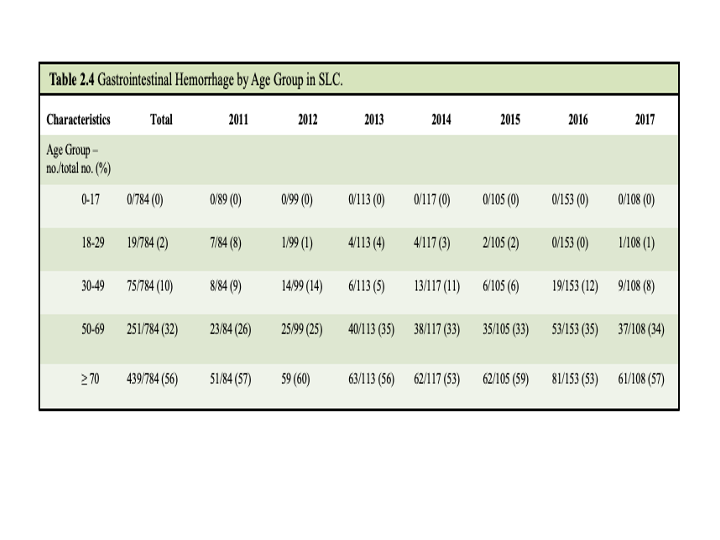

Across the patient cohort, 56% were ≥ 70 years, 32% were aged 50-69 years, 10% were aged 30-49 years, and 2% were aged 18-29 years. The data are shown in Table 2.4.

2.1.3 Intestinal Obstruction

Patient Encounters of Intestinal Obstruction in SLC

There were 1024 hospitalizations for intestinal obstruction in SLC from 2011-2017. The yearly incidence rate for hospitalizations averaged over the 7 years of our study was 130 per 100,000. The national rate for hospital admissions for the condition is 83 per 100,000 [24].

Patient hospitalizations by year are shown in Figure 2.5 and hospitalizations by year and gender are shown in Figure 2.6. The mortality rate was 1.37%. The median length of stay was 3 days. The median cost of treatment for intestinal obstruction admissions was $4,833.

Median Age Range of Intestinal Obstruction in SLC

The median age range of patients hospitalized with intestinal obstruction in SLC from 2011-2017 was 50-69 years. By gender, the median age range in men was 50-69 years with slight variation in individual years. The median age for women was 50-69 years. The data are shown in Table 2.5.

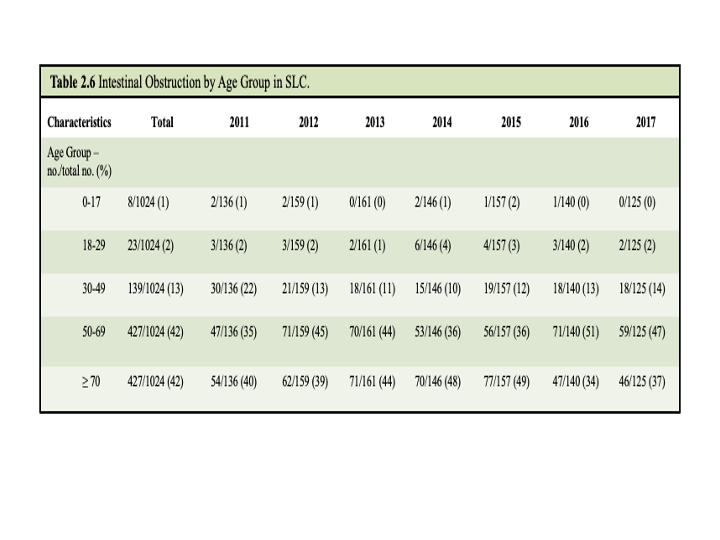

Median patient age is shown in Table 2.5 and specific age breakdowns are shown in Table 2.6. As the table shows, 42% of patients admitted were ≥ 70 years, 42% were aged 50-69 years, 13% were aged 30-49 years, 2% were aged 18-29 years, and 1% were aged 0-17.

2.1.4 Intestinal Infection

Patient Encounters of Intestinal Infection in SLC

There were 708 hospitalizations for intestinal infection in SLC from 2011-2017. The yearly incidence rate of hospitalizations averaged over the 7 years of our study was 90 per 100,000. The national average for hospital admission is 33 per 100,000.24

Patient admissions by year are shown in Figure 2.7 and patient admissions by year and gender are shown in Figure 2.8. The mortality rate was 1.13%. The median length of stay was 3 days. The median cost of treatment for intestinal infection encounters was $4,689.

Median Age Range of Intestinal Infection in SLC

The median age range of patients hospitalized with intestinal infection was 50-69 years. By gender, median age range was also 50-69 for men and women. The data are shown in Table 2.7.

Table 2.8. shows patient hospitalizations by age. Across the cohort, 35% of patients were ≥ 70 years old, 31% were aged 50-69 years, 16% were aged 30-49 years, 9% were aged 18-29 years, and 9% were aged 0-17.

2.2 Discussion

2.2.1 Cancer of Colon

Colon cancer is the most common GI cancer in the United States with an incidence rate of 53.7 per 100,000 [24]. Similarly, cancer of colon was the only GI cancer reported in the top 75% of hospitalized GI conditions in SLC. Averaging 18 hospitalizations per 100,000 residents, the yearly incidence rate of hospital admission is lower in SLC than nationally.

In 2014, it was reported that the median length of stay and median cost for patients with colorectal cancer in U.S. hospitals was 6 days and $16,904 [24]. While the median length of stay in SLC community aligns with the national median length of stay at 6 days, the median cost in St. Lawrence County was 17% less than the national median calculation. The lower cost could be anticipated because SLC hospitals are smaller systems without teaching hospitals that enable a higher DRG reimbursement rate.

The SLC data showed no significant differences in patient encounters by gender. This aligned with national data which shows that colon cancer rates do not differ between men and women [24]. The median age range among women in SLC was higher than the median age in men. This also aligned with the national data. Nationally, the average age of colon cancer diagnosis in men is 68, whereas the average age of diagnosis for women is 72.25 The median age range of colon cancer patients in SLC was 50-69, which is comparable to the national median of 67 years for colon cancer cases [7].

Cancer of colon had the highest mortality rate of GI conditions in SLC (11.1% of all GI mortalities) which is consistent with national mortality rates [24].

2.2.2 Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage

At 99.8 per 100,000, the averaged annual incidence of hospitalization for GI hemorrhage in SLC is lower than the national rate of 161 per 100.000. The median cost to treat GI hemorrhage in the U.S. in 2014 was $6,901 and the median length of stay was 3 days [24]. These values were consistent with our findings for in-patient hospitalizations for GI hemorrhage in SLC. Our finding that the incidence of GI hemorrhage in SLC increases with age was also similar to trends observed nationally [24]. However, while we observed that there was no significant difference in the incidence of GI hemorrhage between men and women in SLC, national trends indicate that the condition has a notable male preponderance [9]. Despite this difference, mortality rates are similar between men and women nationally. Compared with a national mortality rate of 1.2%, our study found that the mortality rate of GI hemorrhage in SLC was 1.53%.

2.2.3 Intestinal Obstruction

At 130.86 per 100,000 the averaged annual incidence of hospitalizations for intestinal obstruction in SLC is higher than the national rate of 83.6 [9]. Our analysis of patient encounters for intestinal obstruction found that the median per patient treatment cost in SLC was $4,833; this cost was approximately 8% lower than the median per patient treatment national cost of $5,273.24 The median length of stay and the average age of hospitalized patients in SLC followed national trends.

National records indicate that the condition is more prevalent in older individuals, particularly after the sixth decade of life. Our finding that the median age range of patients with intestinal obstruction in SLC was 50-69 is in-line with national trends. Our study also found that the mortality rate for intestinal obstruction in SLC (1.37%) was also similar to the national mortality rate of 1.6%. However, while national trends indicated that there was no gender preponderance for the condition, our study found a significantly higher rate of incidence of women hospitalization for intestinal obstruction in SLC.

2.2.4 Intestinal Infection

At 90 per 100,000 the averaged annual incidence of hospitalization for intestinal infection was higher than the national rate of 33.4 per 100,000 [24]. The median treatment cost of intestinal infection in SLC ($4,689) was similar to the national median of $4,305 [24]. In comparison to a national mortality rate of 0.2%, SLC had mortality rate of 1.13%, a rate that is nearly 6 times higher [24]. We found no studies reporting the national rate of intestinal infection by gender. The SLC incidence in women was significantly higher than men. While national records indicated that intestinal infection was not age specific, our study found that the condition was more prevalent with age in SLC.

2.3 Conclusion

To our knowledge, this is the first study examining patient encounters for GI conditions among St. Lawrence County Hospitals.

Among high-severity GI conditions in SLC, two conditions deviated from national rates: intestinal obstruction and intestinal infections. SLC has higher rates of hospitalization for intestinal obstruction than the national average and this condition is more prevalent in women than men across SLC. However, costs of treatment and length of stay for this condition were consistent with national averages.

Hospitalization for intestinal infection was also more common in SLC than nationally and the condition had a mortality rate 6 times higher than national rates.

These differences from national rates should be concerning for public health and clinical practice and suggest a need for further research and investigation.

References

1. Cervellin, G., Mora, R., Ticinesi, A., Meschi, T., Comelli, I., Catena, F., Lippi, G. (2016). “Epidemiology and outcomes of acute abdominal pain in a large urban emergency department: retrospective analysis of 5,340 cases.” Annals of Translational Medicine. 2016; 4(19), 362. doi: 10.21037/atm.2016.09.10

2. Potsdam Volunteer Rescue Squad Monthly Report, August 2020.

3. Statewide Planning and Research Cooperative System (SPARCS) [Internet]. New York Department of Health, Available from: https://www.health.ny.gov/statistics/sparcs/. Unless otherwise noted, census data was obtained from U.S. Census Bureau, 2014-2018 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, available at: https://stlawco.org/Departments/Planning/CommunityStatistics/CensusData.

4. Hess, G., Mehra, R., Carls, J., Profant, J., Altenburger, O., Pasenchenko, J., & Acquavella, F. (2018). “0625 US Prevalence of Narcolepsy and Other Sleep Disorders From 2013-2016: A Retrospective, Epidemiological Study Utilizing Nationwide Claims.” Sleep. 2016; 41(suppl_1), https://doi-org.ezpxy-web-p-u01.wpi.edu/10.1093/sleep/zsy061.624

5. Manfra-Levitt, M. G. (2019). A Study of Breast Cancer Comorbidities and Apoptosis in T47D Breast Cancer Cells (Undergraduate Major Qualifying Project No. E-project-042419-112820). Retrieved from Worcester Polytechnic Institute Electronic Projects Collection: https://digitalcommons.wpi.edu/mqp-all/7071/

6. Rious, M. A. (2017). Bacilus subtilis as a probiotic: Implications for Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Intestinal Colonization of Cadida albicans (Major Qualifying Project No. E-project-042717-114332). Retrieved from Worcester Polytechnic Insitute Electronic Projects Collection: https://digitalcommons.wpi.edu/mqp-all/1318/

7. Dragovich, T. Colon Cancer [Internet]. Medscape, 2021, Available from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/277496-overview

8. Cancer Stat Facts: Colorectal Cancer [Internet]. NIH National Cancer Institute, Available from: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/colorect.html

9. Cagir, B. Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding [Internet]. Medscape, 2019, Available from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/188478-overview

10. Upchurch, B. Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding (UGIB) [Internet]. Medscape, 2019, Available from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/187857-overview

11. Cagir, B. Intestinal Pseudo-Obstruction [internet]. Medscape, 2018, Available from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/2162306-overview

12. Lin, B. Viral Gastroenteritis [Internet]. Medscape, 2018, Available from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/176515-overview

13. Diskin, A. What are the noninfectious causes of gastroenteritis? [Internet]. Medscape, 2017, Available from: https://www.medscape.com/answers/775277-176871/what-are-the-noninfectious-causes-of-gastroenteritis

14. Hall AJ, Rosenthal M, Gregoricus N, Greene SA, Ferguson J, Henao OL, Vinjé J, Lopman BA, Parashar UD, Widdowson MA. Incidence of acute gastroenteritis and role of norovirus, Georgia, USA, 2004-2005. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011 Aug;17(8):1381-8. doi: 10.3201/eid1708.101533.

15. Abdominal Wall Hernias [Internet]. Michigan Medicine University of Michigan, Available from: https://www.uofmhealth.org/conditions-treatments/surgery/abdominal-wall-hernias

16. Rather, A, Abdominal hernias [Internet]. Medscape, 2019, Available from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/189563-overview

17. Ghoulam, E. Diverticulitis [Internet]. Medscape, 2019, Available from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/173388-overview

18. Ghazi, L. Crohn Disease [Internet]. Medscape, 2019, Available from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/172940-overview

19. Rendi, M. Crohn Disease Pathology [Internet]. Medscape, 2017, Available from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1986158-overview

20. Basson, M. Ulcerative Colitis [Internet]. Medscape, 2019, Available from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/183084-overview\

21. Gastroenteritis [Internet]. Medline Plus, Available from: https://medlineplus.gov/gastroenteritis.html

22. Craig, S. Appendicitis [Internet]. Medscape, 2018, Available from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/773895-overview

23. Everhart JE. Overview. Digestive diseases in the United States: Epidemiology and Impact. US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1994; NIH Publication No. 94-1447 pp. 1–53

24. Peery AF, Crockett SD, Murphy CC, et al. Burden and Cost of Gastrointestinal, Liver, and Pancreatic Diseases in the United States: Update 2018. Gastroenterology 2019;156(1).

25. Colorectal Cancer: Risk Factors and Prevention [Internet]. ASCO, 2021, Available from: https://www.cancer.net/cancer-types/colorectal-cancer/risk-factors-and-prevention#:~:text=Colorectal%20cancer%20can%20occur%20in,and%20for%20women%20is%2072

26. Beadles CA, Meagher AD, Charles AG. Trends in Emergent Hernia Repair in the United States. JAMA Surg 2015;150(3): 194-200. Doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.1242

27. Olmi S, Uccelli M, Cesana GC, et al. Laparoscopic Abdominal Wall Hernia Repair. JSLS : Journal of the Society of Laparoscopic & Robotic Surgeons 2020;24(1).

28. Jenkins JT, O’Dwyer PJ. Inguinal hernias. BMJ 2008;336(7638):269–72.

29. Ruhl CE, Everhart JE. Risk Factors for Inguinal Hernia among Adults in the US Population. American Journal of Epidemiology 2007;165(10):1154–61.

30. Lynch WD, Hsu R. Ulcerative Colitis. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459282/

31. United States Census [Internet]. Census. [cited 2021 May 6];Available from: https://www.census.gov/glossary/#term_Populationestimates

32. Cost estimates obtained from New Choice Health. www.newchoicehealth.com

Shanna Bonanno is a PhD student in Bioengineering at Northeastern University in Boston MA. She graduated from Worcester Polytechnic Institute in 2021 with degrees in Biomedical Engineering and Professional Writing.

Mark Bright Bray is a Rosetta Commons Post-baccalaureate Fellow at the University of Denver in Denver, CO. where he is studying protein-protein/RNA/DNA dynamics and their role in human disease progression. He is also interested in public health, social and health equity, healthcare policy, and science communication. Mark can be contacted at https://linktr.ee/markbray.