Epidemiological Study of Gastrointestinal Admissions to St. Lawrence County Hospitals: An Introduction

Shanna Bonanno & Mark Bray

Original Research, Diseases and Outcomes

Abstract

Epidemiological Study of Gastrointestinal Admissions to St. Lawrence County Hospitals: An Introduction

Background

Abdominal complaints constitute approximately 7-10% of all Emergency Department (ED) visits in the United States [1]. In St. Lawrence County (SLC), New York, abdominal complaints constitute approximately 14% of 911 calls [2]. Yet, abdominal pain remains a vague and non-specific complaint, and to date, no study has examined the epidemiology of gastrointestinal diseases in SLC. We conducted a retrospective, descriptive, cohort study to examine and report anonymous, aggregated data summarizing inpatient discharges with a primary APR MDC Description “Diseases and Disorders of the Digestive System” in SLC hospitals from 2011-2017.

Methods

Data were obtained through the open-source hospital inpatient data (SPARCS de-identified) system on the New York Department of Health government website [3]. Case data included SLC inpatient discharges of patients aged greater than 18 years and an APR MDC coded as “Diseases and Disorders of the Digestive System.” Data were downloaded into Microsoft Excel sheets by year and aggregated by diagnosis for analysis.

Results

A total of 8,115 individual inpatient encounters for GI conditions were recorded among the SLC hospitals between 2011-2017. The study focused on the top 9 diagnoses by occurrence, and findings were divided into 2 sections: conditions of higher and lower severity. This introductory article will report the overall analysis of the top 9 GI conditions by hospitalization. The following 2 articles in this series will report detailed analyses for 4 higher-severity conditions and 5 lower-severity conditions.

The 9 GI diagnosis comprised a total of 6,096 patient discharges or 75% of all GI discharges from St. Lawrence County Hospitals between 2011-2017. Among these patients, the median age range was 50-69 years, 44.5% were male, and 55.5% were female. The median length of stay for these conditions was 3 days. The total reported cost for these 9 GI conditions over 7 years was $44,138,148 or an average of $6,305,449 per year and an average of $7,241 per hospitalization. The mortality rate was 0.89% over the study period, representing an average of 7.7 deaths per year. Seventy-nine percent (79.25%) of admissions were rated minor to moderately severe, while 18.52% and 2.23% of admissions were rated major and extreme severities.

Conclusion

Hospital admissions for GI conditions constitute a heavy disease burden across SLC costing on average approximately $6 million each year. While the mortality rate for these conditions remains low, hospitalizations are frequent and women appear to be hospitalized more frequently for GI conditions than men. During the period examined, diverticulitis had the highest incidence of hospitalization while colon cancer was the most severe diagnosis and had the highest median cost and length of patient stay.

A better understanding of the epidemiology of abdominal conditions in Northern New York populations can help guide population health policies, prevention and community health planning, and potential new clinical infrastructures that in combination can work to improve the health of residents living in these rural and remote communities.

Epidemiological Study of Gastrointestinal Admissions to St. Lawrence County Hospitals: An Introduction

1.1 Background

Studies have shown that acute abdominal pain (AAP) is one of the most common complaints brought to the ED. Abdominal pain complaints comprise 7-10% of all ED visits [1]. Yet abdominal pain is often a vague and non-specific complaint with multiple etiologies that complicate recognition and treatment. To our knowledge, the incidence and prevalence of abdominal conditions within the SLC patient population has not been studied. At a general level, a better understanding of the epidemiology of abdominal conditions in Northern New York populations can help guide population health policies, prevention and community health planning, and potential new clinical infrastructures. Clinically, we hope that these studies will contribute to greater awareness and recognition of GI conditions in NNY patient populations, especially among providers for whom epidemiological data is not widely available [1].

Following similar studies, [1,4-6] the goal of this study is to investigate the epidemiological and clinical factors associated with abdominal pain symptoms in a rural community. Subsequent studies (published below) will detail higher- and lower-severity abdominal hospitalizations by incidence and presenting symptoms and will compare findings to national rates. Higher-severity conditions include cancer of colon, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, intestinal obstruction, and intestinal infection. Lower-severity conditions include abdominal hernia, diverticulitis, regional enteritis and ulcerative colitis, noninfectious gastroenteritis, and appendicitis. In this introductory report, we provide a brief description of these 9 conditions and we describe the impact of GI conditions on SLC hospitals including the number of cases, age and gender distribution, cost and lengths of hospital stay, discharge status, APR severity, and mortality for the diagnostic group as a whole (Diseases and Disorders of the Digestive System).

1.1.1 Cancer of Colon

Colon cancer, with symptoms including iron-deficiency anemia, rectal bleeding, abdominal pain, and intestinal obstruction, is the most common type of gastrointestinal cancer.7 The disease has a multifactorial etiology influenced by genetics, environmental stimuli, diet, and inflammatory conditions within the gastrointestinal tract. Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) and hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer syndrome (HNCCS) lead to a 40% risk lifetime risk of developing colon cancer and an almost 100% risk of developing the disease by the age of 40.7 Poor nutrition, excessive alcohol consumption, cigarette smoking, and inflammatory bowel diseases, such as Crohn’s disease, can increase the risk of colon cancer. Colon cancer in the United States has an annual incidence rate of 2.4% of the population and a death rate of 2.2%.8 While gender is not an influential factor in colon cancer, age is a prominent factor with a median age at diagnosis of 67 years [8].

1.1.2 Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage

For clinical purposes, gastrointestinal (GI) hemorrhage is subdivided into 2 categories: lower GI and upper GI hemorrhage. They are distinct in their epidemiology, management, and prognosis [9].

Lower GI Hemorrhage (LGIH)

LGIH is an acute condition, a frequent cause of hospital admission, and contributes to considerable hospital morbidity and mortality, particularly among elderly patients. The condition accounts for 20-33% of episodes of GI hemorrhage, with an annual incidence rate of 20-27 cases per 100,000 population in Western countries [9]. In the United States, the annual incidence is estimated to be 20.5 patients per 100,000 (24.2 in males vs 17.2 in females). LGIH requiring hospitalization represents less than 1% of all hospital discharges [9]. Symptoms include fever, dehydration, abdominal cramps, and hematochezia (blood in the stool). Patients of advanced age are more likely to experience painless bleeding and minimal symptoms.

The condition has a notable male preponderance and has a higher prevalence among older populations, especially after the third decade of life [9]. In addition, studies show that diverticulosis, angiodysplasia, colitis, carcinoma, and anorectal disease—diseases that are more common in older individuals—play roles in the pathophysiology of GI hemorrhage [9].

Upper GI Hemorrhage (UGIH)

UGIH is an acute, potentially life-threatening abdominal emergency that remains a common cause of hospitalization.10 Symptoms of UGIH include hematemesis, melena, hematochezia, syncope, dyspepsia, epigastric pain, heartburn, diffuse abdominal pain, dysphagia, weight loss, and jaundice.10 The condition has an annual incidence of 100 cases per 100,000 population and is four times as common as LGIH [10].

Due to its acuity, UGIH is a major cause of morbidity and mortality, with mortality rates ranging from 6-10% of all cases [10]. UGIH may be caused by peptic ulcer disease, arterial hemorrhage, mucosal deep tears, or low-pressure venous hemorrhage. It is common to find H. pylori infection in UGIH cases as the bacteria is strongly associated with peptic ulcer disease [10]. Aside from peptic ulcer disease, other theorized UGIH etiologies describe a process of weakening and necrosis of the arterial wall, leading to the development of a pseudoaneurysm; the weakened arterial wall is more likely to rupture and produce a hemorrhage [10]. Mucosal tears may also be induced by vomiting, retching, coughing, or straining. While mortality rates of UGIH are similar between men and women, the condition is twice as prevalent in men and increases with age [10].

1.1.3 Intestinal Obstruction and Pseudo-Obstruction

While intestinal obstruction refers to a mechanical (physical) obstruction within the intestine, the term intestinal pseudo-obstruction describes symptoms similar to a mechanical obstruction but without empirical evidence of an actual physical obstruction [11]. Intestinal pseudo-obstruction is an idiopathic condition (of unknown origin) and may be divided into acute and chronic forms; patients presenting with acute intestinal pseudo-obstruction are at high risk of perforation, peritonitis, and death as the colon may be massively dilated [11]. When perforation occurs, the mortality rate can be as high as 40% [11].

The prevalence of the condition remains low. A study of 13,000 orthopedic and burn patients reported a prevalence of 0.29% but noted that the prevalence of intestinal pseudo-obstruction in patients undergoing major orthopedic surgery may be as high as 0.65-1.3% [11]. The incidence of intestinal pseudo-obstruction remains largely unknown because of the possibility of spontaneous resolution. The condition has no gender preponderance, but is more prevalent in older individuals, especially after the sixth decade of life [11]. Risk factors for intestinal pseudo-obstruction include trauma (especially retroperitoneal), serious infection, cardiac disease, recent surgery, spinal cord injury, neurologic disorders, hypothyroidism, electrolyte imbalances, respiratory disorders, renal insufficiency, and severe constipation [11].

1.1.4 Intestinal Infection

Intestinal infection, also known as gastroenteritis, is an inflammation of the lining of the intestines caused by viruses, bacteria, or parasites [12]. Symptoms include dehydration and self-limited watery diarrheal illness (usually lasting < 1 week) associated with symptoms of nausea, vomiting, anorexia, malaise, or fever [12]. Gastroenteritis can be caused by fecal-oral transmission of contaminated food and water, though its pathophysiology remains unclear [13]. Acute gastroenteritis is caused most often by noroviruses, accounting for 19-21 million cases annually [14]. While contraction of an intestinal infection is not age-specific, studies have shown noroviruses are the common cause of infection in adults, while rotaviruses commonly cause infection in children [14].

1.1.5 Abdominal Hernia

Abdominal hernias occur when an organ protrudes through the abdominal wall, typically leaving a visible lump [15]. Symptoms range from mild pain and discomfort to severe pain, nausea, vomiting, and localized redness [15]. Generally, increased pressure in the abdominal cavity can influence the formation of a hernia. Pressure increase can be caused by various conditions including obesity, heavy lifting, peritoneal dialysis, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [16].

More than 1 million abdominal hernia repairs are performed each year in the United States with inguinal hernias accounting for 75% of cases [16]. Inguinal hernias have a male to female ratio of 7:1.16 Umbilical hernias comprise 14%, incisional or ventral hernias comprise 10%, and femoral hernias comprise 3-5% of all hernias. Incision or ventral hernias have a female to male ratio of 2:1.16

1.1.6 Diverticulitis

Diverticulitis refers to the presence of diverticula, small pouches in the large intestinal wall, that are the result of the inner colonic wall pushing out on weaknesses in the outer wall. Symptoms include abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, constipation or obstipation, fever, flatulence, and bloating [17]. The condition is the third most common inpatient gastrointestinal diagnosis in the United States [17]. Its prevalence is estimated at 180 cases per 100,000 people and its incidence increases with age, with individuals over the age of 85 having a 65% chance of developing the disease [17]. Diverticulitis is more common in men than women for individuals under 50; however, there is a slight female preponderance between ages 50 and 70, and a marked female preponderance above the age of 70 [17].

1.1.7 Regional Enteritis and Ulcerative Colitis

Regional enteritis (also known as Crohn’s disease), and ulcerative colitis (UC) are the two primary forms of inflammatory bowel disease. Regional enteritis is a chronic, inflammatory bowel disease that mostly affects the terminal ileum, but can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract from the mouth to the anus [18,19]. Symptoms are wide-ranging and include abdominal pain that is often relieved by defecation, prolonged non-bloody diarrhea, malabsorption symptoms, low-grade fever, general fatigue and malaise, and constipation and obstipation as a result of stricture formation and progressive bowel wall thickening [19]. The prevalence among U.S. adults is 201 per 100,000 and 43 per 100,000 in U.S. children [19] Two peaks of incidence are observed in the general population: one in late adolescence or early adulthood, and another in the 60-to-70-year age group [19].

UC mainly affects the large bowel. Symptoms are similar to those of regional enteritis and include lower abdominal pain, frequent stools, and rectal bleeding [20]. Like regional enteritis, the exact etiology of UC is unknown but potential contributing factors include genetic and environmental factors, immune system reactions, and use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [20]. In the United States, the condition has an annual incidence rate of 10.4-12 cases per 100,000 people and a prevalence rate of 35-100 cases per 100,000 people [20]. The condition is slightly more common in women than in men and has a bimodal age of onset, similar to regional enteritis [20].

1.1.8 Noninfectious Gastroenteritis

Gastroenteritis is irritation or an infection of the digestive tract, particularly the stomach and small intestine [21]. Primary causes of noninfectious gastroenteritis can include ischemic and ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, and carcinoid tumor [21]. Acute viral gastroenteritis can occur at any age with severe cases seen bimodally in the young and the elderly [21]. Acute gastroenteritis has a prevalence of 179 million each year in the United States with 600,000 hospitalizations and 5,000 deaths [21].

1.1.9 Appendicitis

Appendicitis is caused by inflammation within the appendix. Symptoms include abdominal pain, nausea, anorexia, vomiting, and diarrhea or constipation [22]. Severe appendicitis can restrict venous or arterial blood flow or cause rupture and infection. The condition is common in the United States, with an incidence rate of 110 cases per 100,000 and a prevalence of 7%. Appendicitis has a slight male preponderance, and its incidence rises from birth, peaks during the late teen years, and gradually declines in the geriatric years [22].

1.2 Methods

This retrospective cohort study used open-source, de-identified Hospital Inpatient Data obtained through the New York State Department of Health Statewide Planning and Research Cooperative System (SPARCS) to examine and report on adult (age > 18 years) inpatient encounters for abdominal pain in SLC from 2011-2017 [3].

Data were selected and aggregated using the APR MDC Code 6, “Diseases and Disorders of the Digestive System” and the Hospital County “St Lawrence.” Results were downloaded to Microsoft Excel. Data were organized in tabular format by year. Each tab consisted of entries for the categories: Hospital Service Area, Hospital County, Operating Certificate Number, Permanent Facility ID, Facility Name, Age Group, 3-digit Zip Code, Gender, Race, Ethnicity, Length of Stay, Type of Admission, Patient Disposition, Discharge Year, CCS Diagnosis Code, CCS Diagnosis Description, CCS Procedure Code, CCS Procedure Description, APR DRG Code, APR DRG Description, APR MDC Code, APR MDC Description, APR Severity of Illness Code, APR Severity of Illness Description, APR Risk of Mortality, APR Medical Surgical Description, Payment Typology 1, Payment Typology 2, Payment Typology 3, Birth Weight, Emergency Department Indicator, Total Charges, and Total Costs.

Data from each year were compiled into a separate Microsoft Excel sheet and a count of each diagnosis was obtained. To streamline data analysis, CCS Diagnosis Descriptions that had multiple names were combined. For example, CCS Diagnosis Descriptions Cancer of Colon and COLON CANCER were renamed Cancer of Colon, to allow for consistent categorization. The full list of re-categorizations of CCS Diagnosis Descriptions may be found in Table 1 of the Appendix.

Data were cleaned by removing the following categories: Hospital Service Area, Hospital County, Operating Certificate Number, Permanent Facility ID, CCS Diagnosis Code, CCS Procedure Code, APR DRG Code, APR MDC Code, APR Severity of Illness Code, and Birth Weight. The categories were excluded to remove redundancies in the dataset. The operating certificate number and permanent facility identification categories were removed since these correlated to the facility name category, which was kept in the study. The CCS procedure code, APR DRG code, APR MDC code, and APR severity of illness code categories were all removed because the qualitative descriptive inputs for each of the categories were retained.

The dataset was ranked and ordered by the number of hospitalizations for each gastrointestinal disorder. In an effort to report diagnoses that were significant to the population, we selected those diagnoses that represented the top 85% of all diagnoses and which also constituted 2% or more of all conditions. We removed the CCS Diagnosis Description Other gastrointestinal disorders because it was non-specific. Using the cut-off, the top 11 diagnoses were selected, representing the top 75% of diagnoses from the dataset. This gave us the opportunity to examine the data year-to-year and across years.

The full list of rank-ordered diagnosis descriptions may be found in Table 2 of the appendix. The diagnosis category Gastritis and Duodenitis was combined with Intestinal Infection due to clinical presentation and treatment similarities. Abdominal pain was included in the total count of diagnoses but excluded from our analysis because it was considered a symptom instead of a diagnosis. In all, 9 diagnoses categories were examined.

Using Tableau Software and Microsoft Excel, we examined the data for demographic information and analyzed trends in diagnosis-specific encounters. We then compared SLC hospitalization rates to admission rates reported in the general United States population [24]. The top 9 diagnoses were ranked by severity and outcome —the proportion of encounters categorized as severe, major, moderate, or minor—to determine which conditions would be considered high severity versus low severity. Figure 1, below, demonstrates this distribution. Higher-severity diagnoses were determined by mortality rate and proportion of encounters rated as APR levels “extreme,” and “major.” Similarly, lower-severity diagnoses were determined by the proportion of encounters rated as APR level “minor.” We used the Data Analysis Tool in Microsoft Excel to perform Two-Sample T-tests Assuming Unequal Variances and Two Factor ANOVA tests without replication. We used these tests to determine statistically significant differences between groups in our dataset.

1.3 Results

Demographics of Case Study Population

The initial query generated 8,115 hospitalizations. After cleaning the data following the procedure outlined in the methods, the data consisted of 6,096 hospitalizations, which represented 75% of the initial query. We calculated an estimated annual average incidence of 776.68 hospitalizations for GI conditions per 100,000 residents across SLC.

The patients in this data set received medical care at a St. Lawrence County hospital in northern New York between 2011-2017. Table 1.1 lists encounters by age. Consistent with national trends, hospitalizations for GI conditions increased with age: 68% of hospitalization were with patients greater than 50 years old while 43% of the county is older than 45 years [3].

According to U.S. Census Bureau, the sex ratio for the county is 50.8% male and 49.2% female. The population cohort for this study consisted of 44.5% men and 55.5% women, or a 0.8:1 M:F ratio.3 Yearly (averaged) incidence rates by sex were 430.9 cases (per 100,000) for women and 345.8 cases (per 100,000) for men. These data show a higher rate of hospitalizations for women for GI conditions in SLC than for men.

Gastrointestinal Care Expenses

As shown in Figure 1.1, the reported total cost of the 9 conditions for all SLC hospitals over the study duration was $44,138,148 with an average cost of $6,305,449 per year. The median cost was per encounter was $7,240.

Rate of Mortality and Length of Patient Stay

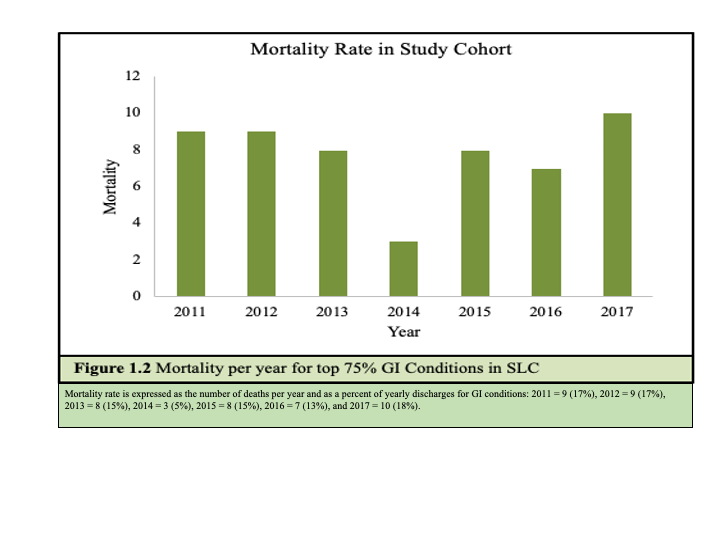

As shown in Figure 1.2, the mortality rate for the 9 conditions over the study period was 0.89% (54 patient deaths), or 7.7 deaths per year. The median length of patient stay across all conditions was 3 days.

APR Severity

Most admissions were rated moderate (46%) or minor (33%) in severity. Extreme cases totaled 2% of admissions and 19% of admissions were rated major severity. The breakdown of severity by year is shown below in Table 1.2.

Patient Disposition

The patient disposition for the majority of patients (5,073 or 83%) was home or self-care. The remaining 17% (1,023) were categorized into 7 different patient disposition categories as shown in Figure 1.3.

1.4 Discussion

We examined 6,096 GI associated SLC hospital discharges from 2011-2017. The discharges represented 75% of hospitalizations coded as “Diseases and Disorders of the Digestive System.” At 55.6 cases per 100,000 residents (556 per 10,000), the GI conditions reported here are relatively common across St. Lawrence County, more common than COPD, asthma, diabetes, congestive heart failure, and drug-related hospitalizations [3]. These conditions are typically mild to moderate in severity and at discharge, the majority of the patients (83.2%) were sent home or sent home with a self-care plan. With nearly 70% of the patients reported at or over the age of 50, the data somewhat aligns with national trends for GI conditions, where higher rates are consistently observed among persons aged 65 years and older [23,24]. However, the research also suggests that hospitalization incidence rates in St Lawrence County may be higher among middle aged adults (50-65) than national averages.

Rates of GI encounters were 24% higher for women in St. Lawrence County. This finding largely aligned national trends reported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), which found rates that incident rates were approximately 20% higher for women than men. Though, the NIDDK data were for age-adjusted ambulatory care visits only [23].

We found that the cost per patient admission for GI conditions in SLC was about 30% less than the national average [24]. Whereas the average national cost of a GI hospitalization per patient reported by Perry et. al was $10,164, SLC spent on average $7,240 per admission. The median length of stay for in-patient hospitalizations in SLC was also in-line with national in-patient hospitalization data reported by Perry et. al [24].

In paper 2, we report the epidemiological results from the study for the 4 higher severity GI conditions: cancer of colon, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, intestinal obstruction, and intestinal infection. In paper 3, we report the epidemiological results from the 5 lower severity GI conditions: abdominal hernia, diverticulosis, regional enteritis and ulcerative colitis, noninfectious gastroenteritis, and appendicitis.

We hope that our findings will find an audience for public health, policy planning, and clinical assessment. From a public health and policy planning perspective, GI conditions represent a common health condition throughout SLC costing the system, on average, $6,305,449 per year. GI conditions may also be early-stage diagnosis that, while relatively mild at first presentation, can result in more serious and costly complications. Our findings provide support for dedicated GI services and increased awareness of the burden of GI diseases throughout the county. Services can address prevention through diet, nutrition, exercise, and proactive attention to the societal determinants that can lead to GI diseases. Our findings also support proactive screening for common GI conditions and an awareness that these conditions appear more commonly among women and at slightly younger ages among SLC residents than national rates may suggest.

Clinically, we hope that our findings can inform early awareness, recognition, diagnosis, and management of these conditions. We particularly hope that our research can inform pre-hospital (EMS) care where roughly 14% of encounters are related to undifferentiated abdominal pain.2 Understanding these conditions, their etiology and presentation, and the demographics associated with their prevalence and severity can help pre-hospital clinicians recognize acute and life-threatening events. With greater knowledge of the range, severity, and frequency of GI conditions, pre-hospital care can help foster appropriate triage and treatment and contribute to greater patient outcomes, satisfaction and trust in the medical system.

References

1. Cervellin, G., Mora, R., Ticinesi, A., Meschi, T., Comelli, I., Catena, F., Lippi, G. (2016). “Epidemiology and outcomes of acute abdominal pain in a large urban emergency department: retrospective analysis of 5,340 cases.” Annals of Translational Medicine. 2016; 4(19), 362. doi: 10.21037/atm.2016.09.10

2. Potsdam Volunteer Rescue Squad Monthly Report, August 2020.

3. Statewide Planning and Research Cooperative System (SPARCS) [Internet]. New York Department of Health, Available from: https://www.health.ny.gov/statistics/sparcs/. Unless otherwise noted, census data was obtained from U.S. Census Bureau, 2014-2018 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, available at: https://stlawco.org/Departments/Planning/CommunityStatistics/CensusData.

4. Hess, G., Mehra, R., Carls, J., Profant, J., Altenburger, O., Pasenchenko, J., & Acquavella, F. (2018). “0625 US Prevalence of Narcolepsy and Other Sleep Disorders From 2013-2016: A Retrospective, Epidemiological Study Utilizing Nationwide Claims.” Sleep. 2016; 41(suppl_1), https://doi-org.ezpxy-web-p-u01.wpi.edu/10.1093/sleep/zsy061.624

5. Manfra-Levitt, M. G. (2019). A Study of Breast Cancer Comorbidities and Apoptosis in T47D Breast Cancer Cells (Undergraduate Major Qualifying Project No. E-project-042419-112820). Retrieved from Worcester Polytechnic Institute Electronic Projects Collection: https://digitalcommons.wpi.edu/mqp-all/7071/

6. Rious, M. A. (2017). Bacilus subtilis as a probiotic: Implications for Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Intestinal Colonization of Cadida albicans (Major Qualifying Project No. E-project-042717-114332). Retrieved from Worcester Polytechnic Insitute Electronic Projects Collection: https://digitalcommons.wpi.edu/mqp-all/1318/

7. Dragovich, T. Colon Cancer [Internet]. Medscape, 2021, Available from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/277496-overview

8. Cancer Stat Facts: Colorectal Cancer [Internet]. NIH National Cancer Institute, Available from: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/colorect.html

9. Cagir, B. Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding [Internet]. Medscape, 2019, Available from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/188478-overview

10. Upchurch, B. Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding (UGIB) [Internet]. Medscape, 2019, Available from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/187857-overview

11. Cagir, B. Intestinal Pseudo-Obstruction [internet]. Medscape, 2018, Available from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/2162306-overview

12. Lin, B. Viral Gastroenteritis [Internet]. Medscape, 2018, Available from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/176515-overview

13. Diskin, A. What are the noninfectious causes of gastroenteritis? [Internet]. Medscape, 2017, Available from: https://www.medscape.com/answers/775277-176871/what-are-the-noninfectious-causes-of-gastroenteritis

14. Hall AJ, Rosenthal M, Gregoricus N, Greene SA, Ferguson J, Henao OL, Vinjé J, Lopman BA, Parashar UD, Widdowson MA. Incidence of acute gastroenteritis and role of norovirus, Georgia, USA, 2004-2005. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011 Aug;17(8):1381-8. doi: 10.3201/eid1708.101533.

15. Abdominal Wall Hernias [Internet]. Michigan Medicine University of Michigan, Available from: https://www.uofmhealth.org/conditions-treatments/surgery/abdominal-wall-hernias

16. Rather, A, Abdominal hernias [Internet]. Medscape, 2019, Available from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/189563-overview

17. Ghoulam, E. Diverticulitis [Internet]. Medscape, 2019, Available from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/173388-overview

18. Ghazi, L. Crohn Disease [Internet]. Medscape, 2019, Available from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/172940-overview

19. Rendi, M. Crohn Disease Pathology [Internet]. Medscape, 2017, Available from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1986158-overview

20. Basson, M. Ulcerative Colitis [Internet]. Medscape, 2019, Available from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/183084-overview\

21. Gastroenteritis [Internet]. Medline Plus, Available from: https://medlineplus.gov/gastroenteritis.html

22. Craig, S. Appendicitis [Internet]. Medscape, 2018, Available from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/773895-overview

23. Everhart JE. Overview. Digestive diseases in the United States: Epidemiology and Impact. US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1994; NIH Publication No. 94-1447 pp. 1–53

24. Peery AF, Crockett SD, Murphy CC, et al. Burden and Cost of Gastrointestinal, Liver, and Pancreatic Diseases in the United States: Update 2018. Gastroenterology 2019;156(1).

Shanna Bonanno is a PhD student in Bioengineering at Northeastern University in Boston MA. She graduated from Worcester Polytechnic Institute in 2021 with degrees in Biomedical Engineering and Professional Writing.

Mark Bright Bray is a Rosetta Commons Post-baccalaureate Fellow at the University of Denver in Denver, CO. where he is studying protein-protein/RNA/DNA dynamics and their role in human disease progression. He is also interested in public health, social and health equity, healthcare policy, and science communication. Mark can be contacted at https://linktr.ee/markbray.